Chile is one of the world’s largest copper producers and yet its copper work is practically unknown. "The reason behind such irony," explains Jorge Monares Araya, "is the lack of craft schools in the country, specialised in preserving and transmitting forging techniques that were lost along generations since colonial times." Jorge’s father was one of those few crafting with copper, chiselling folklore jewellery and relief art as tourist souvenirs. Jorge joined his father’s workshop as a teenager in 1976 and years later he started exploring a self-taught forging technique. "My knowledge about forging was limited at the time and there were no craft schools in Chile teaching such techniques." This process of discovery took Jorge down a different, more creative, path which challenged his craftsmanship talent to make him the only Chilean artisan able to reproduce handmade, colonial-period copper cookware and decorative pieces today.

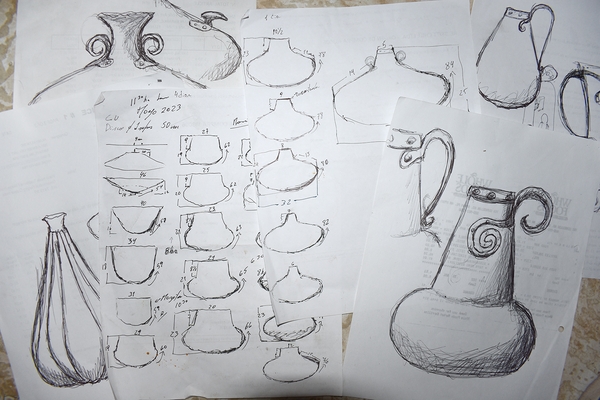

Jorge Monares Araya